cixd creative interaction design lab.

Value Construction with Digital Things

People develop strong attachments to a small selection of the things they encounter in their life. We live in a world increasingly filled with digital things. Some of these digital things are simply physical things that have lost their physical form, such as photos, music, video, and even money. Some are things that never had a lasting physical form, such as email, text, and IM message archives; social networking profile pages including status messages and comments; and personal behavior logs from services such as MapMyRun or FourSquare. Interestingly, digital objects seem different. Imagine a parent reading to a child on a Kindle. Years later would that parent still keep and cherish the device? Or would they cherish a specific digital file? It seems unlikely. We aimed to investigate the opportunities for new products and services to help people to better create, access, and construct value with their digital things. Specifically, we conducted field studies and technology probes with young adults in Europe, North America, and Asia. As a result, we identified the more universal and more culturally specific aspects of value construction with digital things. Based on our findings, we generated ideas for emerging service opportunities at the intersection of cloud, social, and mobile computing in the design of new products and services that help people perceive more value in their digital things.

-

Fragmentation and Transition: Perceptions on Virtual Possessions

Odom, W., Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., López Higuera, A., Marchitto, M., Cañas, J., Lim, Y., Nam, T.-J., Lee, M.-H., Lee, Y., Kim, D., Row, Y., Seok, J., Sohn, B., and Moore, H., “Fragmentation and transition: understanding perceptions of virtual possessions among young adults in Spain, South Korea and the United States,” Proceedings of CHI 2013, ACM Press, (Paris, France, 2012), pp. 1833–1842.Abstract

People worldwide are increasingly acquiring collections of virtual possessions. While virtual possessions have become ubiquitous, little work exists on how people value and form attachments to these things. To investigate, we conducted a study with 48 young adults from South Korea, Spain and the United States. The study probed on participants’ perceived value of their virtual possessions as compared to their material things, and the comparative similarities and differences across cultures. Findings show that young adults live in unfinished spaces and that they often experience a sense of fragmentation when trying to integrate their virtual possessions into their lives. These findings point to several design opportunities, such as tools for life story-oriented archiving, and insights on better forms of Cloud storage.

Image

Video

-

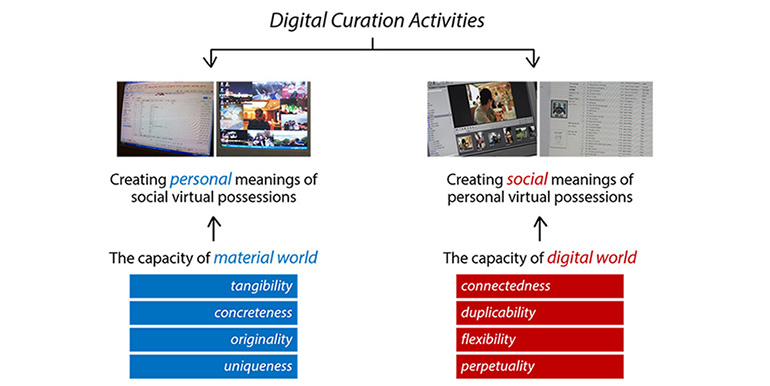

Curation Activities of Creating Personal and Social Meanings for Virtual Possessions

Seok, J., Kim, D., Lim, Y., Nam, T., Lee, M., Lee, Y., Row, Y., Sohn, B., Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., Odom, W., Higuera, A., Marchitto, M., Cañas, J., and Moore, H., “Understanding the Curation Activities of Creating Personal and Social Meanings for Virtual Possessions,” Proceedings of IASDR 2013, (Tokyo, Japan, August 26-30).Abstract

As we can interact with other people through various social applications, we have acquired increasing amounts of virtual possessions that have both personal and social meanings. Unlike material possessions that usually have a clear ownership to a person, the emerging virtual possessions are often created by and shared with multiple people. Thus, the values of such virtual possessions are not only personally, but also socially constructed and cherished. As it becomes important to understand and support the interpersonal contexts where people encounter and acquire various virtual possessions, the present study investigated how people attach personal and social meanings to their virtual possessions. In this paper, we introduce such meaning-making activities with two foci: i) curation activities of creating social meanings of personal virtual possessions, ii) curation activities of creating personal meanings of social virtual possessions. The results of this study will be helpful to consciously think and design the ways to enrich meaningful experiences with digital things.

Image

-

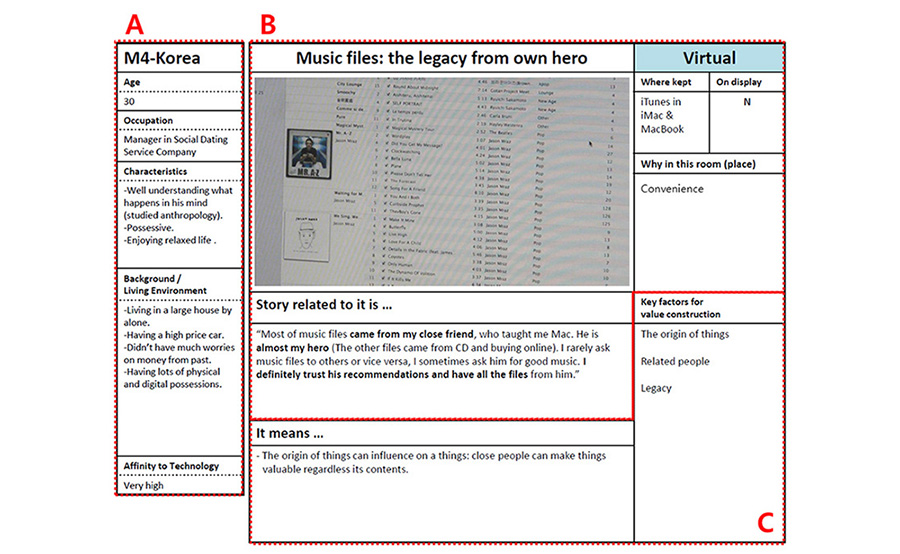

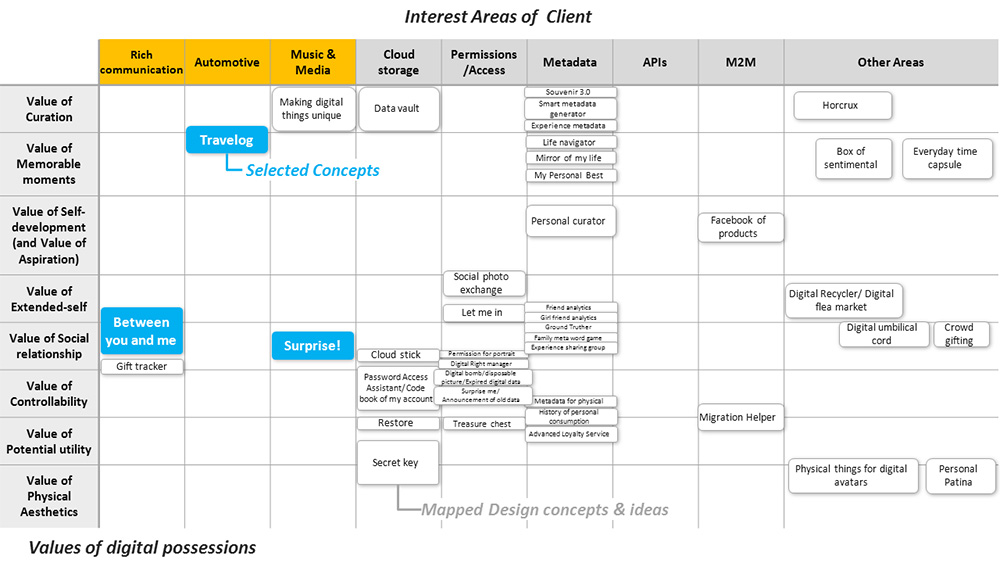

Bridging Research and Practice in Design

Lee, M., Nam, T., Lee, Y., Row, Y., Lim, Y., Kim, D., Seok, J., Odom, W., Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., Higuera, A., Marchitto, M., Cañas, J., and Moore, H. “Bridging Research and Practice in Design: Reflections of the Project on Value Construction with Virtual Possessions,” Proceedings of IASDR 2013, (Tokyo, Japan, August 26-30).Abstract

Design researchers in academia often face the situation where they should achieve both scholarship and practitionership. It is particularly relevant when they undertake corporate-sponsored research projects. As a way to smoothly bridge research and practice in design, we show how design researchers in academia can conduct a project that both advances research and produces an output that a corporate sponsor can operationalize. We introduce an industry-academia collaboration project regarding value construction with virtual possessions. We highlight the procedure and the tools used for transforming research outcomes into useful design resources: insight extraction card, opportunity matrix, and concept delivery card. We discuss barriers to the process and the impacts of our tools. Our investigation into the way the design researchers accomplish meaningful results of research and practice with the process and the tools can help to harmoniously integrate research and practice in design.

Image

Insight extraction card

Opportunity matrix